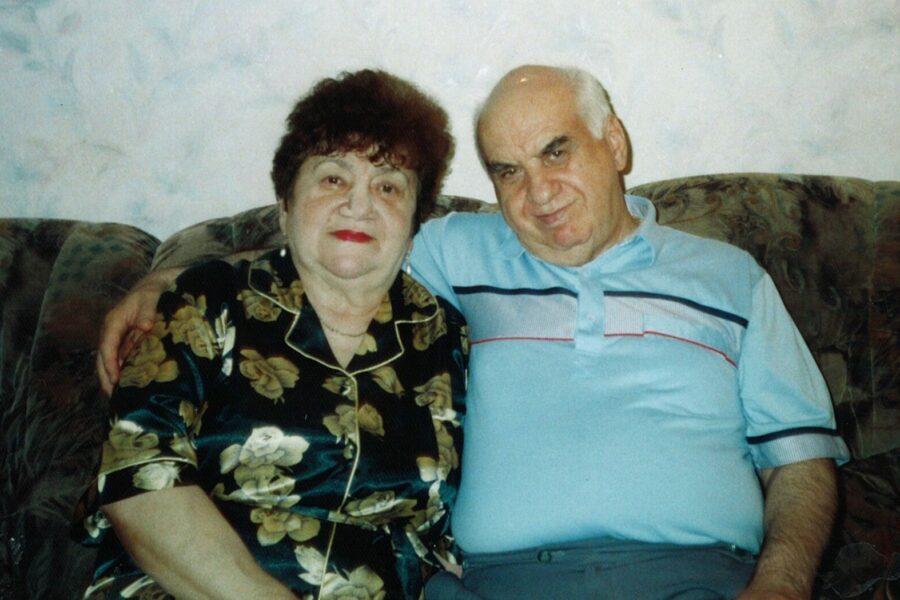

My mother, Dora Solomonovna Zuperman, was born in Minsk in 1916. Before the war, she worked as a teacher. When the war started in 1941, her husband, Samuil Krasilschikov, was drafted into the army. Before leaving he managed to find a place in a truck for his family—his wife, their four-year-old daughter, Mara (Marochka), and his in-laws, Nehama and Shmerl Zuperman—hoping that they would escape the advancing German troops. During an air raid the truck burned down, and my mother and her family had to go back to Minsk.

In Minsk the Germans drove all the Jews to the ghetto. My mother and her family were placed in a small wooden house along with several other families. More than twenty people lived in three tiny rooms and slept on the floor. Every day my mother and other able-bodied people were forced to work on the railroad tracks near the prisoner-of-war camp. One day, my mom saw her brother David among the POWs. She wanted to help him escape from the camp and found some women’s clothes for him, but the next day she found out that David had been hanged. Somebody had revealed to the Germans that he was a Jew.

During the first pogrom in the ghetto, all the people who lived in the house hid in a place under the floor. My mother went into premature labor, and people hiding with her had to clamp her mouth to stifle her cries. If they had been discovered, the Germans and their collaborators, the polizei, would have killed them all. My mom gave birth to a healthy boy, Naum.

While my mom was away working, her father looked after the children. One day, people returning from work were not allowed into the ghetto. While they were kept outside for three days under the threat of being shot, the Germans and the polizei were killing children and old people left in the ghetto. Those who could manage tried to hide. But my grandfather, being deaf, didn’t understand what was going on, and he stayed in the house with six-month-old Naum and the four-month-old son of Mom’s older brother Abram. The polizei shoved my grandfather into the street using their rifle butts. The neighbors said later that he was holding the two boys in his arms as if he held the Torah scroll. The three of them were killed together. By a sheer miracle, Marochka was saved by sixteen-year-old Polina Alperovich. They were in hiding for three days and saw all the killings. This terrible pogrom started on March 2, 1942.

After that, my mom took Marochka with her everywhere, hiding her daughter under the coat on her back. Mom worked at the smithy, whose owner, a German, was a kind man. The Nazis had sent his Jewish wife to the labor camp, and he was sent to the Eastern front. He felt pity for Marochka and gave her hot soup.

When the Germans started to eliminate the ghetto, the first group of prisoners was taken to the town of Trostinets and shot. My mom and Mara were taken with the second group. When the truck carrying them slowed down while turning onto a road outside the city, mom tossed Marochka out as far as possible and then jumped off the truck. Other prisoners followed her. The polizei killed most of them, but some managed to escape.

There were rumors that Jewish partisans were in the Naliboki Forest near Minsk, but my mom and Mara stumbled upon Byelorussian partisans who at first suspected them of spying and wanted to shoot them. Eventually the partisans let them go and showed them the way to the Jewish partisan group led by Zorin. Consisting mostly of old people, women, and children, this group had a small fighting unit that operated together with the Bielski group. Life in the partisan group was very hard physically, but emotionally it was much easier than being in the ghetto.

After the liberation of Minsk, my relatives returned home. My mom was a very knowledgeable and experienced educator. She was the first among the draftsman-ship teachers to receive the highest government award, Honored Teacher of the Belorussian Republic. Mara became a doctor, an obstetrician/gynecologist who saved the health and even the lives of hundreds of women. After emigrating to the U.S. in 1989, she worked in a hematology lab in Skokie, Illinois, until her last day.

Written by Nata Andinysh, Never Heard, Never Forget: Vol. I, 2017