Yad Vashem: Courtesy of Leslie Bell from the Yehuda and Lola Bell (Bielski) Family Collection.

Jewish men and women, many of them teenagers, escaped ghettos and labor camps and joined the resistance.

20,000 –30,000 Jews joined resistance groups in German-occupied Eastern Europe, joining hundreds of thousands of non-Jewish partisans fighting the Germans. Not always welcome in partisan groups because of antisemitism, Jewish fighters often concealed their identity or formed separate units.

Partisans blew up Nazi supply trains and destroyed power plants and factories, focusing their attention on military and strategic targets.

Partisans had few arms and little ammunition but were successful in part because they knew the terrain. Most successful missions took place at night.

Living conditions were harsh; partisans died from infection and disease. They begged, borrowed, bribed, and stole whatever they needed in order to survive.

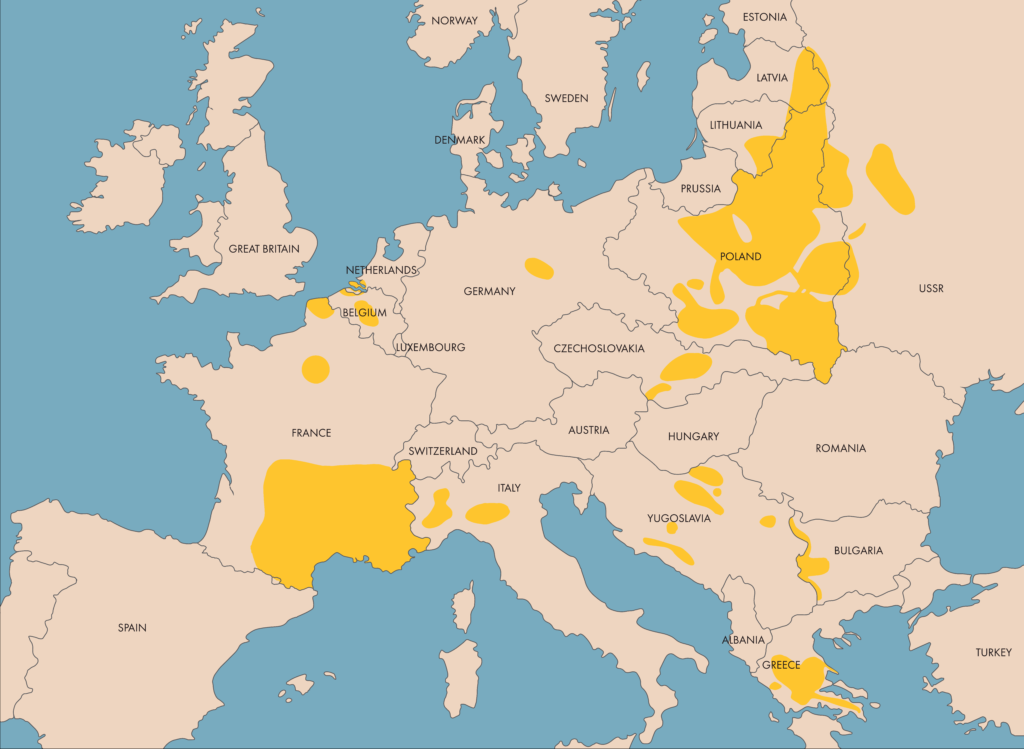

Map of Jewish partisan activity

Jewish partisans were particularly active in German-occupied Poland, the Soviet Union (Belorussia and Ukraine), Lithuania, Greece, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Belgium, both German-occupied and unoccupied France, and Italy.

Partisans hid encampments in forests, swamps, and mountains. In German-occupied Eastern Europe, many partisans lived in underground bunkers called zemlyankas (dugouts): primitive shelters that provided living and hiding space, even through freezing winters.

We came to the underground and we saw Jewish men and women walking around with arms and free. That I said, ‘Oh, if only the Jews in the ghetto would know that eight nights away from here Jews live free.

– Lisa Derman, Partisan

In Eastern Europe, Jews formed their own fighting units or joined other partisan bands.

In German-occupied Russia and Belorussia, Jews were welcomed into partisan units. In German-occupied Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Estonia, and Latvia, where antisemitism was more prevalent, Jews could expect little help from the non-Jewish population.

The best conditions for partisan activity were in German-occupied Belorussia, where vast forests gave excellent cover. The local population supported the partisans, and the Soviet Union assisted with material supplies. Some 10,000 Jews from the Minsk ghetto escaped to nearby forests and joined the partisans.

Dr. Yeheskel Atlas, leader of a partisan unit, asked candidates who wished to join: “What do you want?” The answer: “To die fighting the enemy.”

Courtesy of Beit Lohamei Haghetaot.

The Bielski Family Camp

In December 1941, the Germans murdered thousands of Jews...

…in the Baranowicze region of German-occupied Belorussia, including four members of the Bielski family: mother, father, and two sons. Four sons survived—Tuvia, Asael, Zusya, and Aron—and, along with thirteen other people, fled to the forest near Nowogrodek. Tuvia, the eldest, sent a message to the ghetto: “Organize as many friends as possible. Send them to the woods.”

Over the next two years, this group grew to 1,200 as Jews fled to the forests rather than report for deportation. The Bielskis set up a camp with Tuvia as the commander. His priority was to rescue Jews, regardless of their age or military ability.

The Bielski camp evolved into a small town with kitchens, an infirmary, a school, and workshops. It was the largest Jewish partisan group in the forests and the largest armed rescuer of Jews by Jews.

They survived numerous German raids, killed many enemy soldiers, and lost only fifty members.

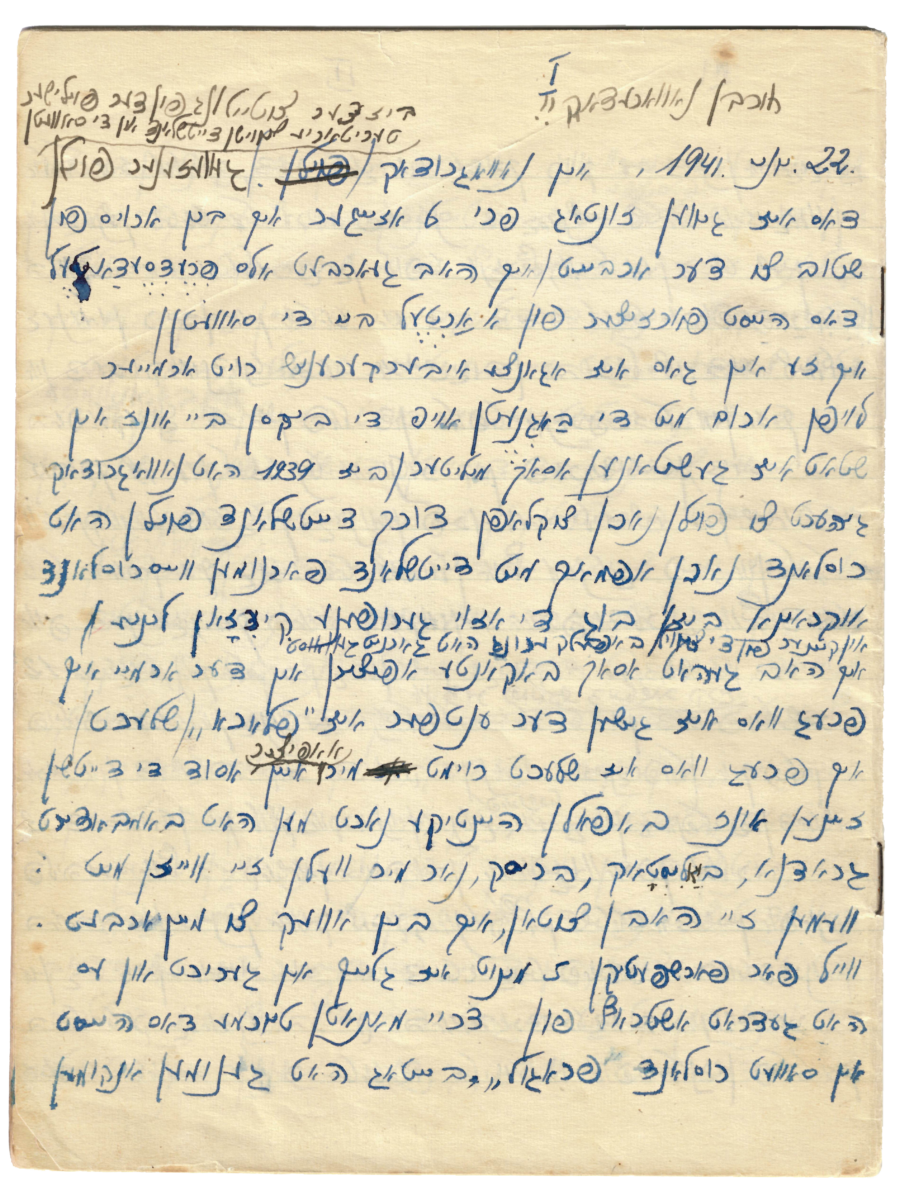

Irving Leavitt’s Partisan Diary

Leavitt was born Israel Janelewitz in Lubcz, Poland in 1910 and grew up in Nowogrodek, Poland.

In 1941, he, along with all the Jews in the area, was forced into the Nowogrodek ghetto. Leavitt escaped, hid in the Lipiczany Forest, and later joined the Bielski partisan camp with his 18-year-old girlfriend, Chaya.

While fighting, Leavitt kept a diary in Yiddish in four school notebooks. In the diary, he details the German invasion of his town and the day-by-day destruction of the Jewish community. Leavitt’s eyewitness account and service in the partisan unit were both forms of resistance to mass murder.

Leavitt and Chaya (Helen) were married in 1945 in Salzburg, Austria.

Irving Leavitt's diary

Below are selections from the translation of Irving Leavitt’s diary. The full diary can be accessed in the Research tab.

Now it’s already eight o’clock, and we don’t see anyone until nine o’clock. Several people rode up to the stream and began drawing water. That’s when we ran out of the little woods and ran over to those people. Everyone was happy to see us. They want to hear news of [those in] the forest. We put on the yellow star, took pails of water, and went with the people to the ghetto. We enter the ghetto through the little gate. We walk in confidently, so as not to draw anyone’s attention.

We prepared the people for their departure, and on the fourth night, we left. At that time, my wife Chaya and my brother, Yakov Motke, and his wife, Sonye, and Leyke were also with us. We left through the fence. We went to Ravniki, crossed the Lider Road, avoided Fetsavits and the camp on the Grodno Road, and went up to the fourteenth kilometer. It was almost daylight. We found the [other partisans] in the forest sleeping.

In a conversation, Tuvia and Asael [Bielski] tell us that in Great Ivia there is a police family, Martsinyevski, whose three sons are policemen in the Nowogrodek police force, but now they have been let go from the force…. They are working in the village as secret agents for the Germans. Twelve Jews from Grodno and Vilna were walking, and they grabbed them as they were going through Ivia. They took them to Nowogrodek, the Jews were shot, and they were rewarded.Planning for Vengeance In a conversation, Tuvia and Asael [Bielski] tell us that in Great Ivia there is a police family, Martsinyevski, whose three sons are policemen in the Nowogrodek police force, but now they have been let go from the force…. They are working in the village as secret agents for the Germans. Twelve Jews from Grodno and Vilna were walking, and they grabbed them as they were going through Ivia. They took them to Nowogrodek, the Jews were shot, and they were rewarded.

We stop at the first house at the entrance to the village, Asael [Bielski] goes over and knocks on the window. Through the window we see a gentile getting out of bed and [he] comes over to the window, opens it up. He is frightened. We ask him what’s going on in the village, if it‘s quiet? We ask him if Germans had come, and if any police had come. He answers that it’s quiet in the village; there have been no Germans and no police either. We ask him for bread and for something to eat with the bread. He gives us two loaves of bread, a white cheese, and some eggs. We thank him very much, politely, and tell him to go [back] to sleep, and we continue on into the village.

Suddenly, I hear a cry: “You swine! You wanted to hide!” I run into the room and see Grisha pulling a lout out of bed. I yell at him, “You dog of a policeman. You wanted to hide!” We rained blows on him and continue to search. We pulled two more out from under their beds. So now we had three. We lit the large hanging lamp in the room. We gathered them all together in a corner of the house and began to berate them in the partisan way accusing them of torturing the Jews in the ghetto during a raid and insisting that they give us weapons. They told us everything and admitted that they took part in the ghetto massacre.

The women and the small children we left in the house, because among ourselves we had decided that we weren’t murderers. We will punish those who murdered our parents, our sisters and brothers. We lay them down on the street near the house, exactly as they had done [to us] in the ghetto and finished them off.

“So did you have mercy on our sisters, brothers, parents and our little children, our innocent lambs? Then there was no feeling of compassion in you. Of your own free will you went to serve the Germans. Murdering and stealing Jewish fortunes. You had a taste for Jewish blood, for Jewish wealth.”