Courtesy of RIA Novosti Photo Library.

Liberation by the Red Army

In late July 1944, the Red Army liberated the Majdanek killing center.

Photographs of the camp were disseminated. On January 27, 1945, the Soviets liberated Auschwitz and found over 6,000 prisoners alive amid horrifying evidence of mass murder and plunder— thousands of men’s suits, more than 800,000 women’s outfits, and over 14,000 pounds of human hair. In the months following, the Soviets liberated more camps in the Baltic states and Poland. Shortly before Germany’s surrender, Soviet forces liberated Stutthof, Sachsenhausen, and Ravensbrueck concentration camps.

Liberators confronted a desperate need for food, medics to aid the sick and dying, chaplains to attend to the living and dead, engineers to purify water, and sanitation crews to clean the filth.

Red Flag Over the Reichstag, 1945

Yevgeny Khaldei

Jewish Ukrainian Red Army photographer, Yevgeny Khaldei, captured this image of Soviet troops raising the Soviet flag over the Reichstag in Berlin. Although the Red Army entered Germany in January 1945, it was not until May 9, 1945, that the Germans finally capitulated following immense loss of life on both sides. With victory, Soviet troops were in control of almost half of Europe.

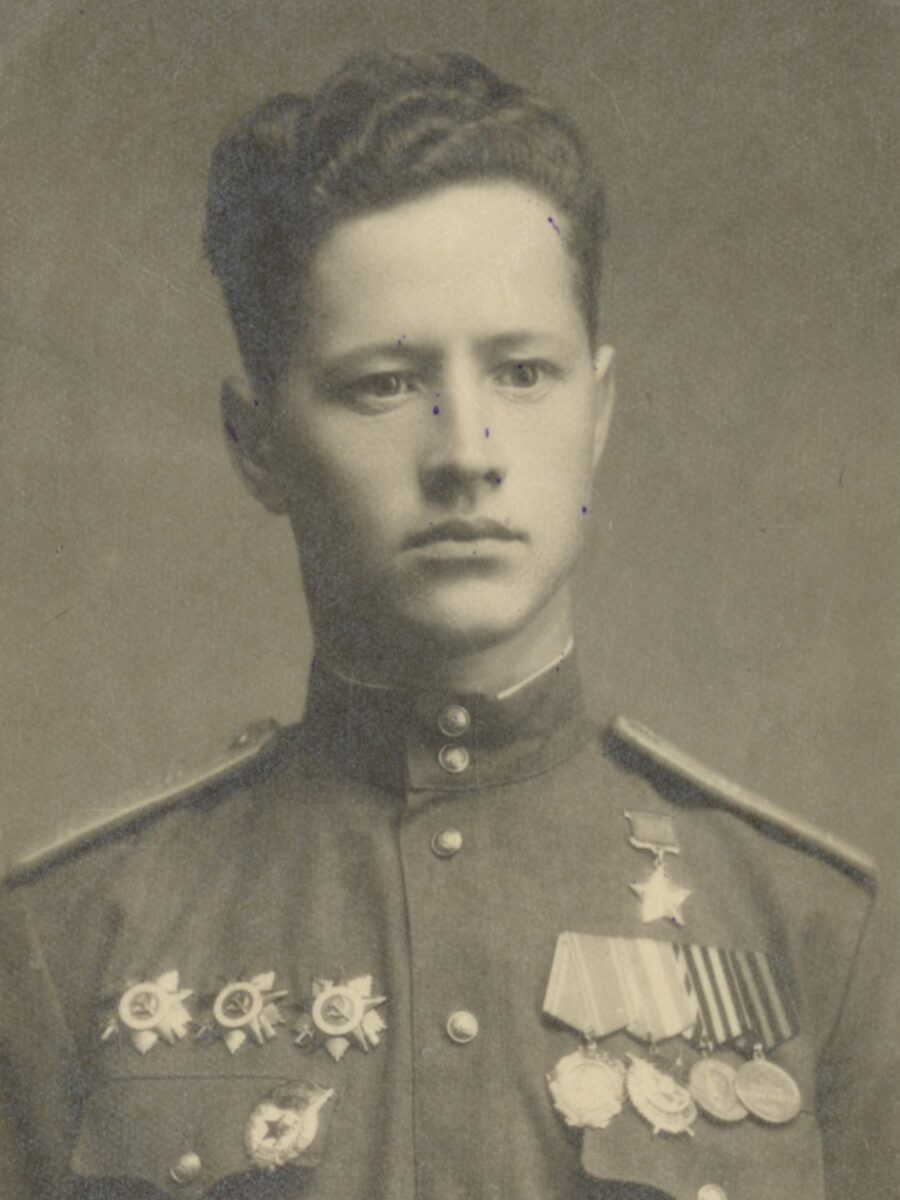

Order of the Patriotic War medal

“For the Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945” medal, and ribbon bar awarded to Mikhail Zhilin for his service in the Soviet Red Army.

Zhilin was interned in the Minsk ghetto, then Maly Trostinets concentration camp from which he escaped. He joined the partisans and eventually the Red Army.

Approximately half a million Jews served in the Soviet Red Army, with thousands serving as officers, including regimental and division commanders. Unlike other armies during WWII, both men and women served in combat.

Stepan Nikolaevich Borozenets

Stepan Nikolaevich Borozenets was born in 1922 and drafted into the Red Army in April 1941. He was an attack pilot in the 4th Assault Aviation Corps and flew more than 100 missions. Borozenets was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union with the Order of Lenin and the Gold Star medal for heroism shown in combat against the Nazis. Borozenets came to Chicago in 1995 for surgery to repair injuries suffered during the war. He was later joined by his wife and son. Borozenets was a member of the Russian American Association of WWII Veterans, and at the time he died in 2016, the only Hero of the Soviet Union living in the U.S.

Peter Polsky

Peter Polsky was born in Kiev, Ukraine in 1922. Prior to WWII, Polsky attended military school. He became an aviation technician and prepared warplanes for flight. By 1943, many Red Army pilots had died or were wounded in combat and Polsky was asked to become a pilot. He flew 12 missions against the Germans, but on the 13th flight, his plane was shot and exploded in midair. Polsky parachuted down but was severely wounded and hospitalized for 5 months. For his service, Polsky was awarded the Order of the Patriotic War, First Class, the Victory Medal Over Germany, and the Victory Medal for the Defense of the Caucasus.

The Liberators

Allied forces had come to defeat their enemy, not liberate prisoners.

Their encounter with Nazi camps and skeletal prisoners was accidental. Even to battle-weary veterans, the horror, stench, and sights were unimaginable.

One soldier recalled, “Many of the men just threw up. Some cried. Some vented their spleen by firing into the guards… .” Soldiers wanted to feed the starving, but survivors could not handle food. One survivor recalled, “Every drop of bread was like if I had 20 needles in my gums.”

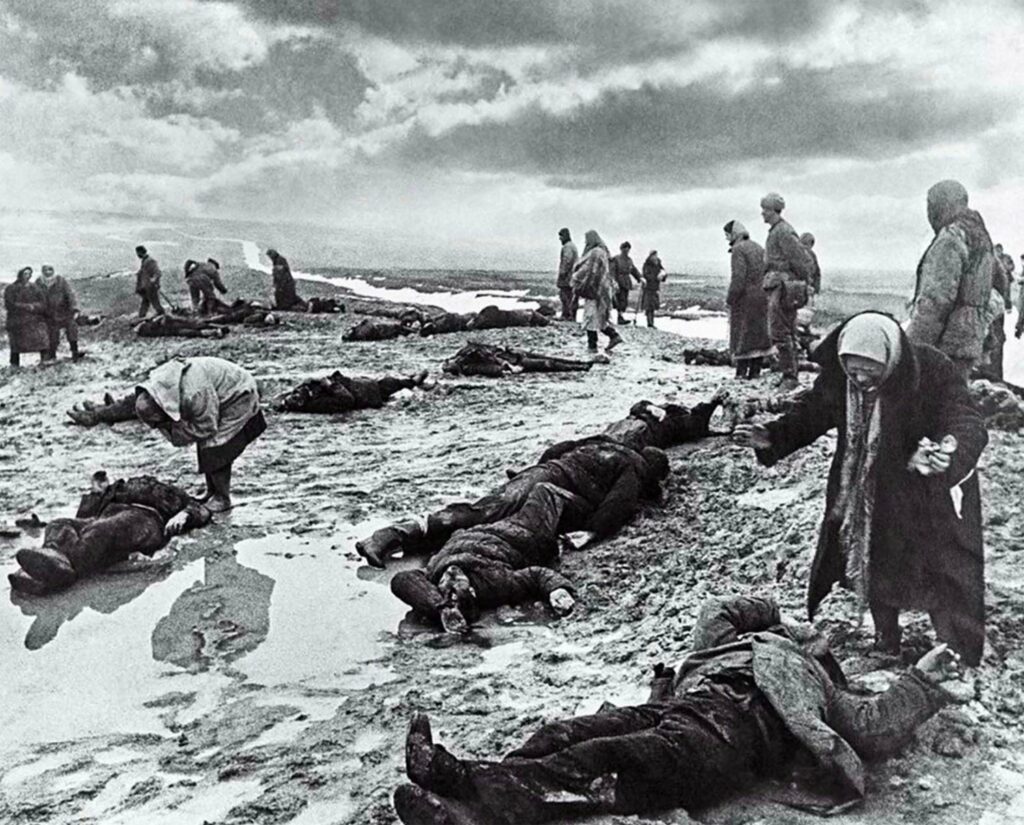

In the Soviet territories, the Red Army discovered mass killing across a vast area – another town wiped off the map, another burial pit outside a town, another scene of absolute destruction.

Photo: Dmitri Baltermants/SIB.

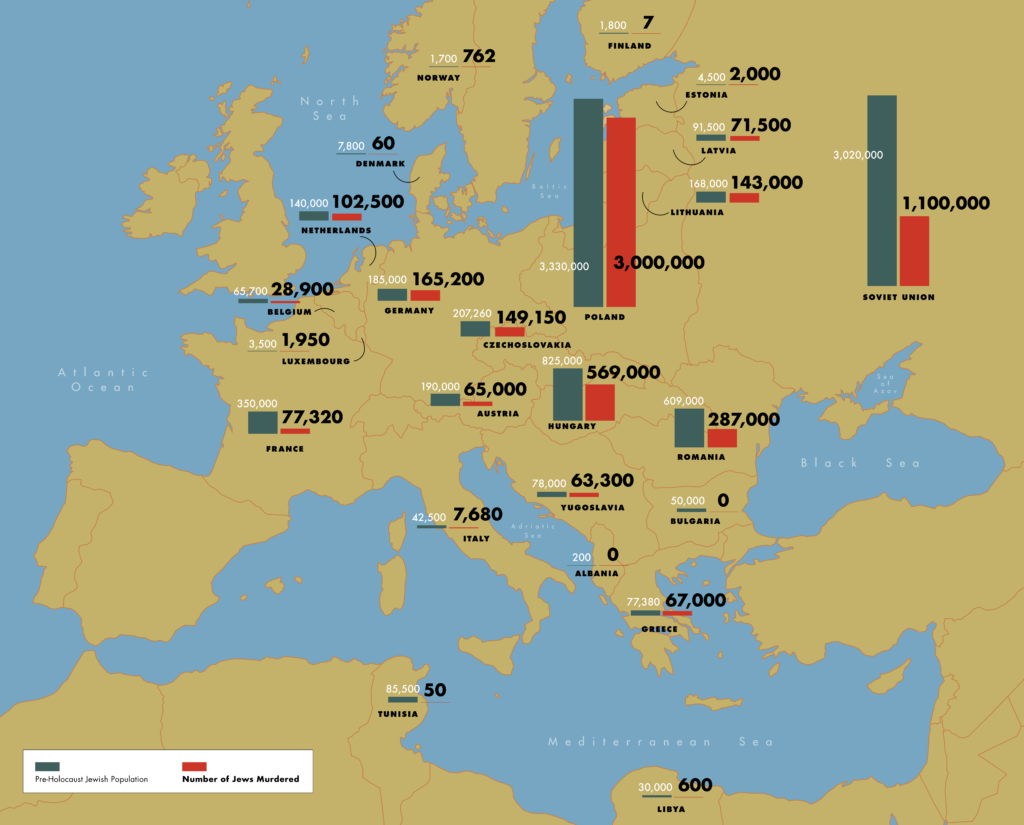

Two-thirds of European Jews murdered in the Holocaust

This map shows the Jewish populations of each country in 1939 and the approximate number of victims per post-war country boundaries. Figures for Germany, Bulgaria, and the Soviet Union and Former Soviet Territories deserve special note. In Germany, many Jews had fled before 1939, decreasing its Jewish population while increasing that of countries to which Jews escaped. In Bulgaria, while its native Jewish population was saved, Bulgarian authorities deported over 11,000 Jews in territory it occupied in Yugoslavia and Greece to Nazi killing centers. In the Soviet Union and German-occupied Soviet Territories, over 2 million Jews were murdered in areas that include parts of Poland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, as well as in the western Soviet Union.

IHMEC: courtesy of Irene Rogers.

The Liberated

Over 27 million Soviets lost their lives in the struggle against the Germans.

Nothing could alleviate the Jewish tragedy of the Holocaust, but Soviet Jews could be proud of the role played by the Soviet Union in defeating Nazism. Jewish contributions to the war effort had been immense.

Soviet evacuation had saved hundreds of thousands of lives, and the defeat of Germany had saved millions. But Soviet Jews had felt antisemitism among some civilians and soldiers during the war. They were aware of collaboration with the Nazis, and they came to realize that the tragedy of the Jewish people was going largely unmentioned in the media and society at large. Soviet Jews looked to the future with a mixture of grief and relief, hope and uncertainty.

Post-war Holocaust memorials

Despite concerted Soviet governmental opposition, survivors initiated memorial projects to honor their murdered families and destroyed communities and gathered to mourn anniversaries of mass murder.

Shown here is a rare example of a memorial to the Jewish victims of Nazism in the Soviet Union. Other memorials conspicuously avoided using the word “Jews” to describe the victims due to the Soviet policy prohibiting drawing specific attention to Jewish suffering under the Nazis and their collaborators.